The Grape in Your Throat

by

David M. Darda

Copyright © 2022

While the question posed in this Gary Larson cartoon (Larson 2022) isn’t likely to show up on the medical board exams, it does illustrate one of those things about our bodies that, while literally right in front of us in the mirror every day, we may never have ever thought about. More likely, this piece of our anatomy is only familiar to us because of cartoon images of characters screaming with their mouths wide open.

That little dangly piece of flesh hanging down way back in the middle of your throat is your uvula. It may not be much to look at, but it’s your very own, it seems to be unique to humans, and it’s got a great name. Anatomists love to name things, and as long as you know a little about word derivation, the multitude of anatomical names actually makes some sense. In this case, the term comes from the Latin uva, which means “grape” – thus the title of this essay.

Structure and Function: How is it built and what do we think it is good for?

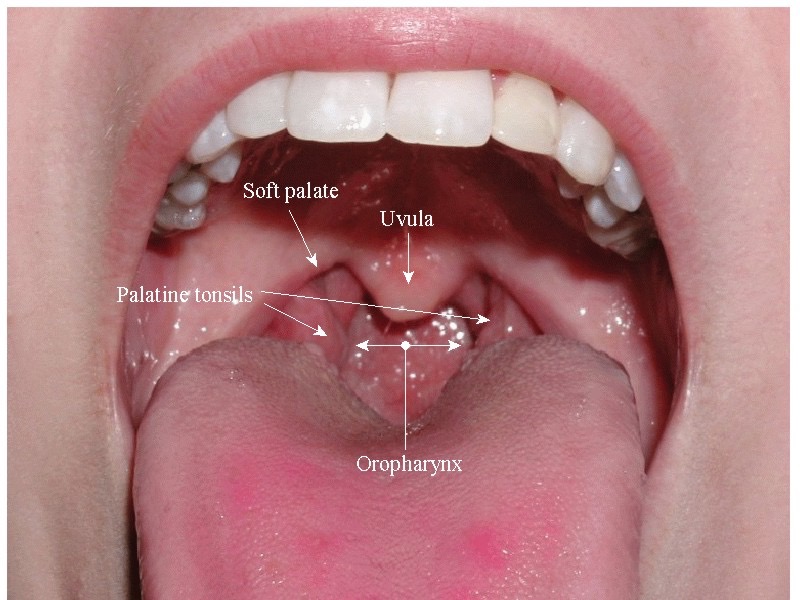

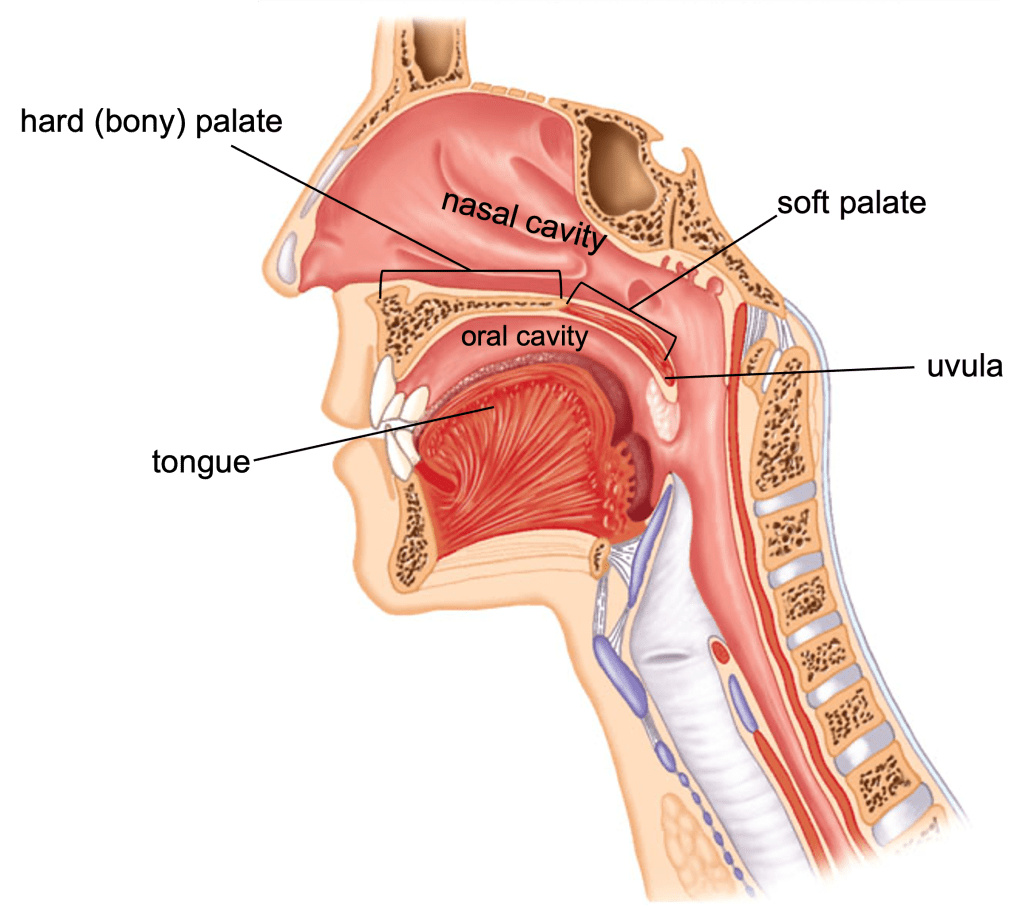

The uvula is not very complicated structurally. It’s basically a piece of soft tissue packed with connective tissue and simple glands with some muscle fibers distributed among them that is connected to the soft palate just anterior to it. The epithelium that covers the underside of the uvula is similar to that of the oral cavity, while the upper surface is covered with an epithelium like the lining of the nasal cavity.

Essentially, the uvula is an extension of the roof of your mouth, what anatomists call the secondary palate. Ancestral vertebrates (e.g., fish, amphibians, reptiles) have a different type of palate, which protects the ventral surface of the brain from the contents of the oral cavity. Since it’s evolutionarily older, it’s called the primary palate, thus making the one we’re talking about the secondary palate. You can get a good idea of the anatomy of your palate by taking the tip of your tongue and running it along the roof of your mouth from front to back. From just behind your teeth for about two inches you can feel the hard or bony palate, which is formed by four bones that come together to form a relatively thin shelf of bone. Behind the hard palate, you will feel your tongue move off the bone and onto soft tissue, the soft palate. Above both parts of the palate is your nasal cavity.

To understand the main function of the secondary palate, just imagine life without it. Think of chewing some nice crispy tortilla chips. Without your secondary palate, all of those rough pieces and that tasty guacamole would not only be in your mouth, but also up in your nasal passages. Not only would that be painful, but it would also mean that you would have to hold your breath until you were done chewing and had swallowed your chips and dip.

So, our secondary palate functions to divide our oral cavity from our nasal cavity, and if you look at all vertebrates, it turns out that the presence of a secondary palate is mostly a mammalian characteristic. The high metabolic rate of mammals requires a high level of oxygen and therefore requires a constant airflow into and out of the lungs. We can’t stop breathing while we chew our food. The secondary palate allows us to multitask – chew and breathe at the same time.

The function of the uvula seems pretty clear if we consider it as merely an extension of the soft palate. As we swallow, the soft palate (and the uvula) is pushed up and back to form a seal and prevent food or drink from sneaking up into the nasal cavity. It works pretty well, although if you’ve ever taken a drink of soda pop and started laughing, you know this seal can be broken!

If all vertebrate soft palates had a uvula extending off the end, that might be the end of the story. What’s curious is that we humans, seem to be the ONLY vertebrate with this extra piece of tissue dangling off the back end of our soft palate. An evolutionary biologist would call this an autapomorphy, which is a term used to refer to an anatomical feature exhibited by a single taxon (in this case a single species, Homo sapiens) within a larger evolutionary group (in this case, the class Mammalia). In laymen’s terms we might call it an oddball feature, and oddball things usually call out for explanation.

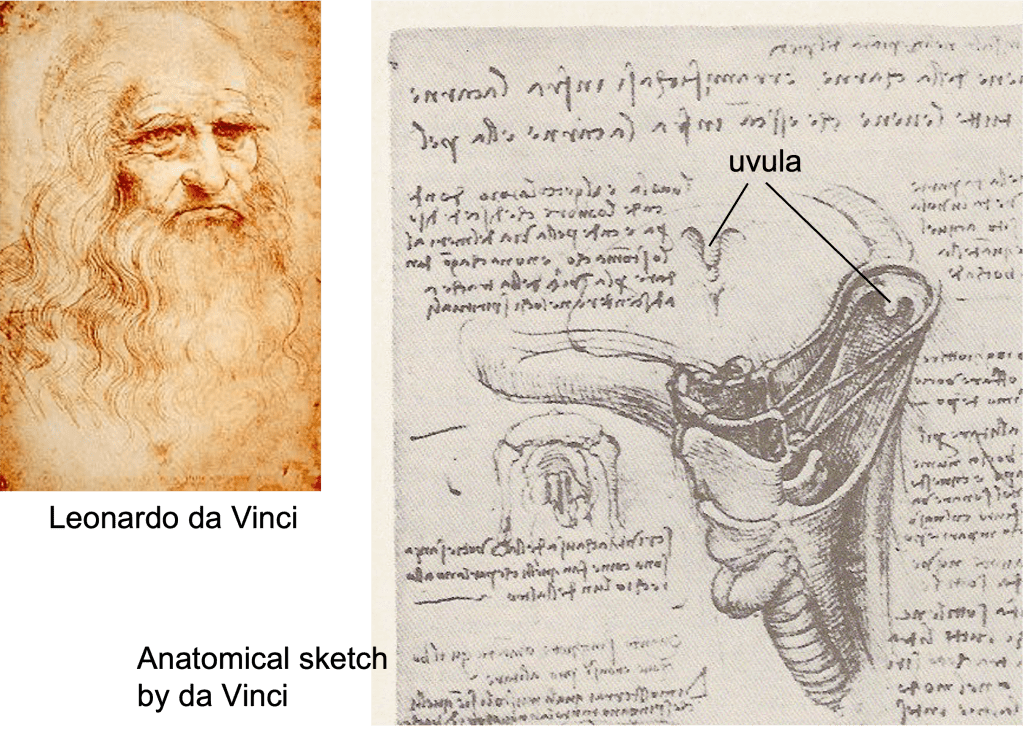

Anatomists have attempted to explain the uvula for a long time. Galen (122-199 AD), one of the fathers of anatomy, believed that the uvula was important in speech and contributed to the beauty of the voice (Fritzell 1969). Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 AD) wrote that, “The uvula is the drip-stone whence drips the humor which descends from above and which falls by way of the oesophagus into the stomach. It has no occasion to go by way of the trachea to the spiritual regions.” This is based on the belief at the time that excess fluid from the brain and pituitary gland drained into the nasal cavity (da Vinci 1983). While Galen believed that this fluid would drip onto the larynx to lubricate the voice and lungs, Leonardo took the opposite view, that the uvula directed this brain fluid away from the larynx and into the esophagus and on to the stomach, thus avoiding the lungs and the thoracic region where vital spirits resided.

A traditional belief of the Bedouins of the southern Sinai Desert is that the uvula is the source of thirst, and its removal leads to less of a need or desire for water. More scientific ideas of uvular function concern its role in producing certain sounds in human speech, in directing mucus from the nasal passages toward the base of the tongue, in assisting with the immunological response of throat tissue, and in the sensation of temperature to prevent the swallowing of overly hot food (Back et al. 2004).

All these hypotheses respond to our almost automatic assumption that everything has a purpose, an indication of how we have been influenced by the concept of adaptive evolution. I see this all the time in anatomy classes when students ask, “What’s it for?” or “What’s it do?” If a structure exists, we think it must be good for something, or it would have been eliminated by evolution.

Well, to paraphrase Sigmund Freud, “Sometimes a uvula is just a uvula”. It’s sort of like asking what the function of the male nipple is. As far as we know, there is none. Rather, the male nipple exists because it’s a part of mammalian development that responds to female but not male hormones. I like to refer to such structures as phylogenetic (evolutionary) baggage.

I always like to entertain the phylogenetic baggage hypothesis and have had it in mind for the past 30 years when my students asked me why we have a uvula and the cats we were dissecting didn’t. Maybe that little piece of tissue is just a little piece of tissue, an extension of the soft palate and nothing else.

I haven’t been alone in this line of thinking, but one of the more creative phylogenetic baggage hypotheses was suggested by A.E. Ewens in a 1934 paper in which he suggested that the uvula is merely a vestigial remnant of a more extensive soft palate which served as a protective curtain in the throat of animals to prevent insects and other foreign objects from getting into the throat while running through the forest (Ewens 1934). This seems an unlikely explanation for a couple of reasons. First, and we’ll get back to this, embryological development would suggest that the uvula is an evolutionary addition, not a leftover from our ancestors. Second, this hypothesis suggests that only humans retain this vestigial structure even though we’re surely not the only animal to run around the forest. Maybe we’re the only one who doesn’t know when to keep our mouth shut!

Testing Functional Hypotheses: What is it really good for?

A true examination of function requires more than casual observation and conjecture. It takes detailed analysis, comparison, and if possible, experimentation. Yehuda Finkelstein, an Israeli otolaryngologist and researcher, and his colleagues have done all of this regarding the uvula, and they did not limit their analysis to the human condition (Finkelstein et al. 1992). They examined the detailed anatomy of the soft palates of sheep, cows, horses, dogs, cats, pigs, macaques, baboons, and chimpanzees, as well as humans. Macroscopic examination of these specimens showed that only the human has a uvula.

Histological examination (microscopic study of the tissue and its cells) showed that the human uvula is packed with mucous glands. This was not surprising when comparing to the soft palate tissue of the other mammals, which also had mucous glands. However, the human mucous glands were seromucous glands. As opposed to “regular” mucous glands, seromucous glands secrete a much higher volume of a more watery fluid.

So, Finkelstien et. al. present some very nice detailed anatomical analysis and put it in a phylogenetic perspective. Obtaining experimental data on humans is of course a much dicier proposition. What happens if you remove the uvula? Well, you can’t just go around asking people if they would mind if you cut out their uvula and then see how it affects their speech or if they get corn chips and soda pop up their nose when they swallow. (Well, I suppose you could ask….)

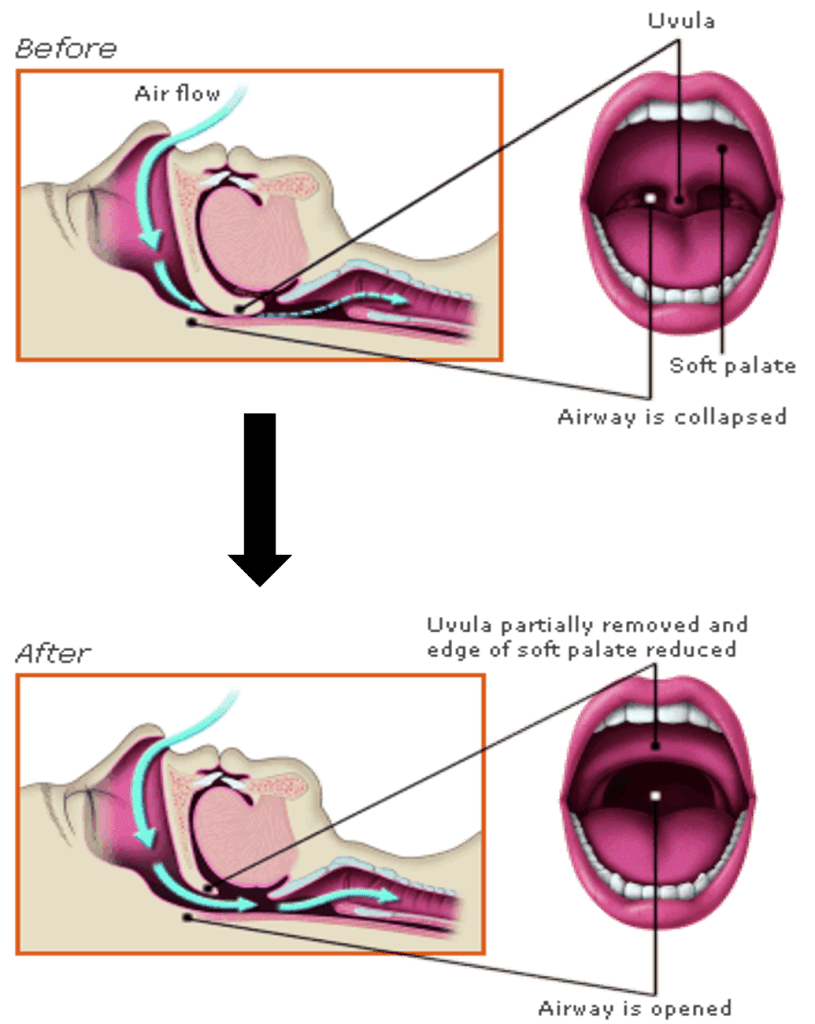

As it turns out, we don’t have to ask people to do this. Some people choose to do it! Specifically, some people with obstructive sleep apnea, a condition in which the tissues of the throat become enlarged to the point that during sleep, these tissues obstruct the airflow into the trachea and lungs – not a good thing! Mild sleep apnea can lead to poor sleep and daytime sleepiness while severe sleep apnea over time can deprive the body of oxygen to such an extent to cause serious physiological damage. While there are a number of treatments for

obstructive sleep apnea, the one of interest here is uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), which involves removal of the uvula, at least a portion of the soft palate, and usually other excess tissue in the throat region that might relax during sleep and constrict and even close a person’s airway. The success of this “roto-rooter” treatment seems to be variable, but for our purpose here it results in an experimental group of people without a uvula (but with a heck of a sore throat for a few days).

Once healed, these uvuless folks seem to have a period of adjustment to life with a shortened soft palate. There are sometimes minor problems with reflux of food or drink into the back of the nasal cavity and some minor changes in voice quality. Since the seal between the oral and nasal cavities is disrupted, there is some leakage of air that interferes with creating the suction needed to drink through a straw or the ability to forcefully blow without air escaping through the nose. Luckily, patients seem to adapt to their new anatomy, and most of these problems disappear in six to nine months. One consequence that seems to linger longer however is dryness and resulting discomfort in the throat, especially associated with talking (Back et al. 2004).

So, it seems we’re back to Galen’s 1800-year-old idea that the uvula is important in the lubrication of the voice. What gives us some confidence in this hypothesis is additive evidence. Evidence from comparative anatomy tells us that the only organism that possesses a uvula also has well-developed vocal cords and relies to a large degree on spoken language for communication. Histological evidence shows that the uvula is packed with glands that produce lots of lubricating mucus and is located so that most of that lubricant bathes the throat and larynx. Experimental evidence shows that without a uvula, lubrication and speech is compromised or at least uncomfortable.

Not only does all of this add up, but in a 2004 study, G.W. Back et al. directly observed the uvula in action using a flexible nasoendoscope. During speech they found that the uvula swings back and forth while secreting saliva, essentially basting the throat, larynx, and vocal cords.

Evolution Process: How did it evolve?

We could end this uvula story here. We know details of its structure, what its function seems to be, why such a function would be adaptive in humans, and we even know why it’s called what it is. But there’s another question we can ask about any body part – where did it come from or how did it get to be that way? The general answer is easy. It evolved – often well before the origin of the human species.

For example, if we think about the evolution of the human secondary palate, the answer is pretty easy. The secondary palate evolved in early mammals, long before humans or any other apes even existed. There have been slight modifications of size and orientation, but essentially your secondary palate is the same as your dog’s, or a chimp’s, or any other mammal’s. We all have one, it’s basically the same, and it serves the same functions. This doesn’t answer the question of the origin of the secondary palate in the first place, but it easily explains ours. We have simply inherited it from our ancestors.

Most human anatomy can be explained similarly, but the uvula is unique to humans and begs the question of evolutionary origin. How did evolution “build” this thing since our divergence from the apes? As far as I know, this question has not been addressed, but I’d like to suggest here that the answer might be found by examining the development of the human secondary palate.

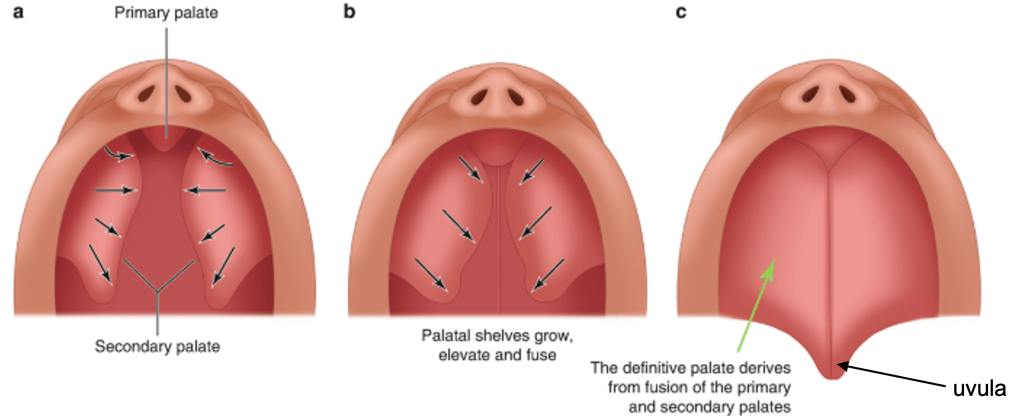

As I mentioned earlier, the hard palate is formed by four bones that grow together during our embryological development. The anterior two bones are a pair of extensions from our upper jawbones. These maxillary bone extensions grow from the sides toward the midline of the oral cavity and in the adult make up about the anterior two thirds of the hard palate. Behind the maxillary bones, a pair of palatine bones grow similarly from the sides toward the midline, and behind the palatines, the soft palate follows suit.

Ultimately, the bones and soft palate fuse and seal along the midline so that the division between oral and nasal cavities is complete. This fusion doesn’t happen all at once; rather it proceeds from anterior (front) to posterior (back) with the maxillaries fusing first, then the palatines, and finally the soft palate. This zipper-like closure begins during the sixth week of our embryonic development and is finished approximately six weeks later.

Unfortunately, this process does not always work properly. If there is not enough tissue in this region or if this growth pattern ends early, the result is the condition known as cleft palate. An extensive cleft palate can extend from the very front of the oral cavity leaving little division between the oral and nasal cavity. The resulting condition is severe and results in problems with nursing and feeding. On the other hand, the process may mostly finish, leaving only the very back of the soft palate with a slight notch or the uvula divided into right and left parts.

Cleft palate of some extent occurs approximately once in 2000 births and is more common in females than males. Cleft palate sometimes runs in families, indicating a genetic component, but it can also be caused by exposure to certain environmental toxins or may be associated with other developmental or genetic conditions (AAO 2022).

Whatever the underlying cause of cleft palate, it essentially results from the truncation of a developmental process, and I think this suggests a possible mechanism for the evolutionary origin of the uvula. If slight truncation of human soft palate development results in a soft palate without a uvula and with an appearance similar to other mammals, might the origin of the uvula be the result of prolonging the same developmental process?

Such hypotheses that implicate changes in developmental timing leading to evolutionary changes in adult anatomy are not new. Embryologists have seen evolution reflected in development for nearly 200 years, and differences in developmental rates of the face and cranium have long been thought to be important in the evolution of the human skull. Until recently, the relationship of evolution and development was mostly implied, but more and more, molecular biologists are making tremendous strides in our understanding of gene regulation and finding the underlying causes of changes in developmental timing. Such evo-devo studies are giving us added insight into how evolutionary changes in anatomical structures occur.

Uvulary lessons

The uvula has proven to be a bit of a surprise to me. I initially thought the uvula would be of interest for three reasons. First, and most personally, I’ve always been amused by it. It’s got a funny name and it’s easy to make jokes about in class. Second, in spite of it being easy to see, I assumed most people hadn’t given their uvula a lot of thought, but would also find it amusing. Third, I hoped to illustrate that even the most obscure little human structure can tell us something about the bigger picture of the function and evolution of form.

Well, I’m still amused by my uvula, but now I see more than just its entertainment value. I have to adjust my attitude on a couple of issues. First, as a comparative vertebrate anatomist, I prefer to illustrate how similar humans are to other vertebrates; how most structures are not unique to us and that we in fact are not much different from those cats in an anatomy lab. Sure, we’re bipedal instead of quadrupedal, have less hair, and our brain is more well-developed (at least in some ways). The uvula, I’m afraid, is an exception. Sometimes we are unique!

My other preconception about the uvula reflects, I think, the timing of my scientific training. As a graduate student in the 1980’s, I came under the spell of Stephen J. Gould and others who suggested that not everything is adaptive (Gould and Lewontin 1979). Some structures exist merely as phylogenetic baggage or as the result of some basic developmental pattern. There is not always a functional or adaptive explanation. In fact, one should make this assumption until evidence can be gathered to show otherwise. This idea is part of my baggage, and a part I hold dear, so my assumption has always been that the uvula is nothing more than an extension of the soft palate with no specific function of its own. Thanks to some good work by a number of uvula enthusiasts, it appears that the uvula is indeed functionally useful, and likely an adaptation associated with our propensity for language and for talking so much.

Additionally, if there is any substance to my idea that the uvula may have evolved by the modification of the process of our palatal development, this amusing little grape-like uvula might even give us insight into the process of the evolution of form. Not bad for something that’s been dangling right in front of us in the mirror each morning.

Literature Cited

AAO (American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery) (2022). Cleft lip and cleft palate. Retrieved from www.entnet.org/content/cleft-lip-and-cleft-palate Accessed 7 December 2022.

Back GW, Nadig S, Uppal S, Coatesworth AP (2004). Why do we have a uvula?: Literature review and a new theory. Clinical Otolaryngology 29, 689-693.

da Vinci L (translations by O’Malley CD, de C. M. Saunders JB) (1983). Leonardo on the human body. New York: Dover Publications.

Ewens AE (1934). An overlooked factor in susceptibility to the common cold. Virginia M. Monthly 61, 40.

Finkelstein Y, Meshorer A, Talmi YP, Zohar Y, Brenner J, Gal R (1992). The riddle of the uvula. Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery 107(3), 444-450.

Fritzell B (1969). The velopharyngel muscles in speech. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 250.

Gould SJ, Lewontin RC (1979). The spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian paradigm: A critique of the adaptationist programme. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 205, 581-598.

Larson, Gary. The Far Side – a website hosted and operated by Andrews McMeel Universal, copyright 2019-2022 FarWorks. https://www.thefarside.com/. Accessed 6 December 2022.